This year's Philadelphia Worldcon, MilPhil, was just the latest event in the long

and storied history of Philadelphia fandom. This next article looks back at some of

this history through the eyes of one of its founding members, Bob Madle. In this

first of a two-part remembrance of his long and illustrious career as a science

fiction fan, Bob describes his personal odyssey, starting with his discovery of

science fiction from futuristic pulp magazine covers in the early 1930s, to the

first-ever science fiction convention in 1936, to the beginnings of the worldcons,

through the war years of the 1940s, to the first Philadelphia worldcon in 1947.

This year's Philadelphia Worldcon, MilPhil, was just the latest event in the long

and storied history of Philadelphia fandom. This next article looks back at some of

this history through the eyes of one of its founding members, Bob Madle. In this

first of a two-part remembrance of his long and illustrious career as a science

fiction fan, Bob describes his personal odyssey, starting with his discovery of

science fiction from futuristic pulp magazine covers in the early 1930s, to the

first-ever science fiction convention in 1936, to the beginnings of the worldcons,

through the war years of the 1940s, to the first Philadelphia worldcon in 1947.

I was not quite a teenager when I

first found my personal 'sense of wonder'. It was 1933, and I was walking past this

back-date store, in Philadelphia where I lived with my parents, and there, in the

window, was a copy of Wonder Stories. The cover of the magazine showed a

giant moon coming towards the earth. It was so fascinating that I just had to have

it, so I ran home and asked my mother for a nickel to buy it. And that's how I

discovered science fiction. I was not quite a teenager when I

first found my personal 'sense of wonder'. It was 1933, and I was walking past this

back-date store, in Philadelphia where I lived with my parents, and there, in the

window, was a copy of Wonder Stories. The cover of the magazine showed a

giant moon coming towards the earth. It was so fascinating that I just had to have

it, so I ran home and asked my mother for a nickel to buy it. And that's how I

discovered science fiction.

Soon thereafter, when I was an active

Boy Scout, my father told me that I needed a new pair of Scout pants and gave me two

dollars. But on the way to the clothing store, I saw this magazine shop and the

whole window was filled with Wonder Stories, Amazing Stories, and

others. I went in there instead, and I spent the whole two dollars on magazines --

they were a nickel apiece or six for a quarter. As you might expect, it resulted in

some real trouble for me. But it did start my science fiction collection. Soon thereafter, when I was an active

Boy Scout, my father told me that I needed a new pair of Scout pants and gave me two

dollars. But on the way to the clothing store, I saw this magazine shop and the

whole window was filled with Wonder Stories, Amazing Stories, and

others. I went in there instead, and I spent the whole two dollars on magazines --

they were a nickel apiece or six for a quarter. As you might expect, it resulted in

some real trouble for me. But it did start my science fiction collection.

It didn't take me too long to discover

there were others who were also interested in science fiction. I liked finding out

what other people thought of the stories I read so I began reading the Readers'

Departments in the magazines, and some of the letter writers soon became as famous

to me as some of the authors. In particular there was one fan, Allan Glasser, who

I really think, historically, can be named as the first real science fiction fan.

He had letters in the old Science Wonder Stories, and had earlier won a

couple of Hugo Gernsback's contests. He wrote some of the most fantastic

letters. It didn't take me too long to discover

there were others who were also interested in science fiction. I liked finding out

what other people thought of the stories I read so I began reading the Readers'

Departments in the magazines, and some of the letter writers soon became as famous

to me as some of the authors. In particular there was one fan, Allan Glasser, who

I really think, historically, can be named as the first real science fiction fan.

He had letters in the old Science Wonder Stories, and had earlier won a

couple of Hugo Gernsback's contests. He wrote some of the most fantastic

letters.

It didn't take me long to decide to

write some letters of my own, but the first letter I ever wrote did not appear in a

science fiction magazine. Gernsback, at the end of 1934, had started a magazine

called Pirate Stories, in which he'd written an editorial that stated that

'We will print stories about pirates of the past, pirates of the present, and, yes,

even pirates of the future'. So I sat down and wrote him a short letter saying that

he should try to get a complete novel by Edmund Hamilton, who could write a great

space pirate story. There was a free subscription to either Pirate Stories

or Wonder Stories if your letter was printed, and so there I was, at age 13,

winning a free subscription to Wonder Stories. I thought that was just

incredible. It didn't take me long to decide to

write some letters of my own, but the first letter I ever wrote did not appear in a

science fiction magazine. Gernsback, at the end of 1934, had started a magazine

called Pirate Stories, in which he'd written an editorial that stated that

'We will print stories about pirates of the past, pirates of the present, and, yes,

even pirates of the future'. So I sat down and wrote him a short letter saying that

he should try to get a complete novel by Edmund Hamilton, who could write a great

space pirate story. There was a free subscription to either Pirate Stories

or Wonder Stories if your letter was printed, and so there I was, at age 13,

winning a free subscription to Wonder Stories. I thought that was just

incredible.

After that I began writing to

Amazing Stories and Wonder, and my first letter to Amazing

appeared in the August 1935 issue. It was also in 1935 that I discovered that not

only were there other science fiction fans around the country, there were even some

in my immediate area. By then Gernsback had started the Science Fiction League; he

had mentioned it in the April 1934 Wonder Stories and in the May issue it

was organized. I didn't join at the time because I didn't have the membership fee,

but in 1935, Milton Rothman and Raymond Mariella announced that they were starting a

Philadelphia chapter of the SFL. I sent a card to them, but for some reason, it

wasn't until September that Milt got in touch with me. After that I began writing to

Amazing Stories and Wonder, and my first letter to Amazing

appeared in the August 1935 issue. It was also in 1935 that I discovered that not

only were there other science fiction fans around the country, there were even some

in my immediate area. By then Gernsback had started the Science Fiction League; he

had mentioned it in the April 1934 Wonder Stories and in the May issue it

was organized. I didn't join at the time because I didn't have the membership fee,

but in 1935, Milton Rothman and Raymond Mariella announced that they were starting a

Philadelphia chapter of the SFL. I sent a card to them, but for some reason, it

wasn't until September that Milt got in touch with me.

By then I had made contact with some

other local fans, and three of them -- John Baltadonis, Jack Agnew, and Harvey

Greenblatt -- and myself had started our own little science fiction club, which we

called the Boys' Science Fiction Club. Baltadonis was really the first fan I got to

know. I'd met him in first grade, and we became friends for life -- we discovered

Tom Swift together; we discovered Edgar Rice Burroughs, and we discovered the

science fiction magazines. We all were meeting once every couple of weeks at my

house; when I finally got in touch with Rothman I found out that for their first

couple meetings only a few people showed up and after that nobody showed up except

him and Mariella. So, in October 1935 we all came over there, along with Oswald

Train, who had just moved to Philadelphia from elsewhere in Pennsylvania, and it

sort of reorganized. That the beginning of the Philadelphia Science Fiction

Society. By then I had made contact with some

other local fans, and three of them -- John Baltadonis, Jack Agnew, and Harvey

Greenblatt -- and myself had started our own little science fiction club, which we

called the Boys' Science Fiction Club. Baltadonis was really the first fan I got to

know. I'd met him in first grade, and we became friends for life -- we discovered

Tom Swift together; we discovered Edgar Rice Burroughs, and we discovered the

science fiction magazines. We all were meeting once every couple of weeks at my

house; when I finally got in touch with Rothman I found out that for their first

couple meetings only a few people showed up and after that nobody showed up except

him and Mariella. So, in October 1935 we all came over there, along with Oswald

Train, who had just moved to Philadelphia from elsewhere in Pennsylvania, and it

sort of reorganized. That the beginning of the Philadelphia Science Fiction

Society.

The seven of us were the founding

members. There were others who attended, too; sometimes we had as many as 12-15

people at meetings. By December, when the club was only a few months old, Rothman

came running over to my house waving this letter he'd just received from Charles D.

Hornig, who was the Managing Editor of Wonder Stories and also the 'Working

Manager' of Gernsback's Science Fiction League. He and Julius Schwartz, who was the

editor of Fantasy Magazine, the leading fan magazine of its time, were coming

to visit us! The seven of us were the founding

members. There were others who attended, too; sometimes we had as many as 12-15

people at meetings. By December, when the club was only a few months old, Rothman

came running over to my house waving this letter he'd just received from Charles D.

Hornig, who was the Managing Editor of Wonder Stories and also the 'Working

Manager' of Gernsback's Science Fiction League. He and Julius Schwartz, who was the

editor of Fantasy Magazine, the leading fan magazine of its time, were coming

to visit us!

Everything in fandom back then

revolved around the professional magazines -- Wonder Stories, Amazing

Stories, Astounding Stories, and to a somewhat lesser extent, Weird

Tales. They were the Big Four, and all of fandom revolved around them. In the

early meetings of the club, we discussed the stories that appeared in those

magazines, and we discussed the authors. What Schwartz's Fantasy Magazine

did was publish interviews with the editors, articles about the authors, columns

telling what stories had been accepted and rejected -- everything was about the

professional magazines. Back then, and unlike today, the prozines were everything.

When Julius Schwartz and Charles D. Hornig came to visit us on a snowy Saturday

afternoon, we all sat around on the floor and they talked about the science fiction

world, telling us many strange and wondrous things. Or so we thought at the time,

anyway. Everything in fandom back then

revolved around the professional magazines -- Wonder Stories, Amazing

Stories, Astounding Stories, and to a somewhat lesser extent, Weird

Tales. They were the Big Four, and all of fandom revolved around them. In the

early meetings of the club, we discussed the stories that appeared in those

magazines, and we discussed the authors. What Schwartz's Fantasy Magazine

did was publish interviews with the editors, articles about the authors, columns

telling what stories had been accepted and rejected -- everything was about the

professional magazines. Back then, and unlike today, the prozines were everything.

When Julius Schwartz and Charles D. Hornig came to visit us on a snowy Saturday

afternoon, we all sat around on the floor and they talked about the science fiction

world, telling us many strange and wondrous things. Or so we thought at the time,

anyway.

In October 1936, once again Rothman

came over to my house waving a letter. This time he had received a letter from

Donald A. Wollheim, who at that time was probably the most well-known fan in the

world. Wollheim was *the* number one fan then, even superior to Ackerman. Wollheim

had stated, in the letter, that he and much of the International Scientific

Association fan club, including such well-known fans of the time as Wollheim himself,

John B. Michel, Frederick Pohl, David A. Kyle, Herbert Goudket, and William S.

Sykora, were planning to come to Philadelphia. The date of the event was to be

October 22nd, and when it arrived, several members of the Philadelphia group --

Rothman, Ossie Train, and myself -- were there at the train station to meet them. In October 1936, once again Rothman

came over to my house waving a letter. This time he had received a letter from

Donald A. Wollheim, who at that time was probably the most well-known fan in the

world. Wollheim was *the* number one fan then, even superior to Ackerman. Wollheim

had stated, in the letter, that he and much of the International Scientific

Association fan club, including such well-known fans of the time as Wollheim himself,

John B. Michel, Frederick Pohl, David A. Kyle, Herbert Goudket, and William S.

Sykora, were planning to come to Philadelphia. The date of the event was to be

October 22nd, and when it arrived, several members of the Philadelphia group --

Rothman, Ossie Train, and myself -- were there at the train station to meet them.

After they arrived, we wandered around

Philadelphia with them and showed them some of the sights. We went over to

Independence Hall and we all signed the book there. And then we went back to

Rothman's home, where Baltadonis and some of the other Philadelphia fans showed up.

Though Dave Kyle claims it was himself that made the proposal, I remember that it

was Wollheim who suggested the event be called a convention. After they arrived, we wandered around

Philadelphia with them and showed them some of the sights. We went over to

Independence Hall and we all signed the book there. And then we went back to

Rothman's home, where Baltadonis and some of the other Philadelphia fans showed up.

Though Dave Kyle claims it was himself that made the proposal, I remember that it

was Wollheim who suggested the event be called a convention.

Wollheim also said we could lay plans

to have a real World's Science Fiction Convention in 1939 in conjunction with the

upcoming New York World's Fair; of course, the World's Fair wouldn't know anything

about it, but we could still say it was in connection with the World's Fair.

So a business meeting was held, Rothman was elected chairman, and minutes were taken

by John B. Michel which were later printed in The International Observer, the

ISA's magazine. Sam Moskowitz, in The Immortal Storm, pointed out that

except for this brief hour or so of formality, the first convention would have

occurred in England in February of 1937. Now, I know that some British fans have

recently claimed that this was done merely as a ploy to stop them from being the

first, but the fact of the matter is that we didn't even know there was going

to be a convention in England! It had nothing to do with us trying to beat them to

it, because we didn't even know they were going to have a convention. Wollheim also said we could lay plans

to have a real World's Science Fiction Convention in 1939 in conjunction with the

upcoming New York World's Fair; of course, the World's Fair wouldn't know anything

about it, but we could still say it was in connection with the World's Fair.

So a business meeting was held, Rothman was elected chairman, and minutes were taken

by John B. Michel which were later printed in The International Observer, the

ISA's magazine. Sam Moskowitz, in The Immortal Storm, pointed out that

except for this brief hour or so of formality, the first convention would have

occurred in England in February of 1937. Now, I know that some British fans have

recently claimed that this was done merely as a ploy to stop them from being the

first, but the fact of the matter is that we didn't even know there was going

to be a convention in England! It had nothing to do with us trying to beat them to

it, because we didn't even know they were going to have a convention.

As for how the first World's Science

Fiction Convention actually came about, it all started with the break in the New

York City fan club, the International Scientific Association. The ISA was formed

in accordance with Gernsback's vision: young people would read science fiction,

thereby becoming interested in science, and eventually become scientists -- that

was the Gernsback ideal. The early clubs like the original International Scientific

Association, and also the Scienceers, which was headed by Allan Glasser, were formed

with that premise in mind all the articles in their club magazines were about

rocketry, how to make a telescope, things like that. But then you began to see

things creep in like: 'We went up to Gernsback's office the other day and here are

some of the stories that are going to appear...'. This was especially true in

Glasser's magazine, The Planet, which was the official organ of The

Scienceers; you could see it was the beginnings of a fan magazine. As for how the first World's Science

Fiction Convention actually came about, it all started with the break in the New

York City fan club, the International Scientific Association. The ISA was formed

in accordance with Gernsback's vision: young people would read science fiction,

thereby becoming interested in science, and eventually become scientists -- that

was the Gernsback ideal. The early clubs like the original International Scientific

Association, and also the Scienceers, which was headed by Allan Glasser, were formed

with that premise in mind all the articles in their club magazines were about

rocketry, how to make a telescope, things like that. But then you began to see

things creep in like: 'We went up to Gernsback's office the other day and here are

some of the stories that are going to appear...'. This was especially true in

Glasser's magazine, The Planet, which was the official organ of The

Scienceers; you could see it was the beginnings of a fan magazine.

But there was trouble at the ISA.

Sykora and Wollheim had a battle on what the ISA was supposed to do and what is it

going to do. Sykora, who at that time was a scientific experimenter first and a

fan second, had wanted to keep it as a scientific experimenters group, but by then

the group was beginning to be loaded down with the pure science fiction fans. Sykora

finally wrote a letter saying to the effect that, 'I watched the organization change

from what I intended it to be into something different because of the sheer activity

of the science fiction fans vs. the sheer inactivity of the scientific

experimenters.' And so he resigned the presidency. But there was trouble at the ISA.

Sykora and Wollheim had a battle on what the ISA was supposed to do and what is it

going to do. Sykora, who at that time was a scientific experimenter first and a

fan second, had wanted to keep it as a scientific experimenters group, but by then

the group was beginning to be loaded down with the pure science fiction fans. Sykora

finally wrote a letter saying to the effect that, 'I watched the organization change

from what I intended it to be into something different because of the sheer activity

of the science fiction fans vs. the sheer inactivity of the scientific

experimenters.' And so he resigned the presidency.

But there was more. After going into

some detail why he was resigning, Sykora then made a startling (to me) announcement

-- he said, "I would like to nominate for the new president, either James Blish or

Robert A. Madle." Here, I had just turned 16, and he was nominating me for

president of the group! At this point, Wollheim -- who was like the 'Master of

Deceit' in the early days of fandom, and could tell when somebody else was trying to

deceive, too -- correctly surmised that Sykora's resignation was intended to get

control of the International Scientific Association out of the New York area, and

have someone else running it. So Wollheim, after Sykora resigned, said, 'As

Treasurer, I am senior officer and am now in charge of the organization, and I am

abolishing it'. And so the ISA passed into history. But there was more. After going into

some detail why he was resigning, Sykora then made a startling (to me) announcement

-- he said, "I would like to nominate for the new president, either James Blish or

Robert A. Madle." Here, I had just turned 16, and he was nominating me for

president of the group! At this point, Wollheim -- who was like the 'Master of

Deceit' in the early days of fandom, and could tell when somebody else was trying to

deceive, too -- correctly surmised that Sykora's resignation was intended to get

control of the International Scientific Association out of the New York area, and

have someone else running it. So Wollheim, after Sykora resigned, said, 'As

Treasurer, I am senior officer and am now in charge of the organization, and I am

abolishing it'. And so the ISA passed into history.

As a result, two former good buddies,

Sykora and Wollheim, were now enemies forever. Sam Moskowitz came onto the scene

about this time and got to be good friends with Sykora. Together, along with James

Taurasi, they started an organization known as New Fandom, which was developed only

to put on the first World's Science Fiction Convention. To gain legitimacy, they

held a one-day convention in 1938 in Newark which had more than 100 people in

attendance. Editors of magazines, such as Campbell of Astounding, looked the

situation over; they had to pick somebody to support for the convention running, and

so they picked Moskowitz and Sykora over Wollheim and his group. The two magazines,

Thrilling Wonder and Astounding, came out in favor of New Fandom for

putting on the first worldcon; the magazines were very interested because it looked

to be good public relations for them, and something that might result in an increase

in their circulation. As a result, two former good buddies,

Sykora and Wollheim, were now enemies forever. Sam Moskowitz came onto the scene

about this time and got to be good friends with Sykora. Together, along with James

Taurasi, they started an organization known as New Fandom, which was developed only

to put on the first World's Science Fiction Convention. To gain legitimacy, they

held a one-day convention in 1938 in Newark which had more than 100 people in

attendance. Editors of magazines, such as Campbell of Astounding, looked the

situation over; they had to pick somebody to support for the convention running, and

so they picked Moskowitz and Sykora over Wollheim and his group. The two magazines,

Thrilling Wonder and Astounding, came out in favor of New Fandom for

putting on the first worldcon; the magazines were very interested because it looked

to be good public relations for them, and something that might result in an increase

in their circulation.

So, when that happened, the Wollheim

group sort of fell to the background, but didn't dissolve completely. They changed

their name to The Futurians, and out of The Futurians came such writers and editors

as Wollheim himself, Robert W. Lowndes, Fred Pohl, and Cyril Kornbluth. And there

was also John B. Michel, who had previously wrote a speech called "Mutate or Die,"

which had seemed to advocate communism as a means for obtaining a utopian society.

Many of The Futurians were active communists at that time. But it really didn't

bother too many fans because it was still the 1930s, and Earl Browder had just

gotten over 80,000 votes in the 1936 election running on the Communist ticket. So, when that happened, the Wollheim

group sort of fell to the background, but didn't dissolve completely. They changed

their name to The Futurians, and out of The Futurians came such writers and editors

as Wollheim himself, Robert W. Lowndes, Fred Pohl, and Cyril Kornbluth. And there

was also John B. Michel, who had previously wrote a speech called "Mutate or Die,"

which had seemed to advocate communism as a means for obtaining a utopian society.

Many of The Futurians were active communists at that time. But it really didn't

bother too many fans because it was still the 1930s, and Earl Browder had just

gotten over 80,000 votes in the 1936 election running on the Communist ticket.

By the time the first worldcon

happened in 1939, the animosity between Wollheim and Moskowitz had become almost

sheer hatred. Moskowitz had become convinced, and he remained so to his dying day,

that the Futurians had intended to cause trouble at the convention. But they were

still told they could come in if they agreed to behave themselves. But just about

this time, a big pack of pamphlets had been discovered, which Moskowitz, Sykora, and

Taurasi considered to be communistic propaganda that would be used to disrupt the

convention. So six of the Futurians Wollheim, Michel, Kornbluth, Lowndes,

Gillespie, and Pohl were turned away at the door, banned from the convention.

Interestingly enough, one of the members of the Futurians who did get in was

David A. Kyle, who was the guy who had written and printed that pamphlet! By the time the first worldcon

happened in 1939, the animosity between Wollheim and Moskowitz had become almost

sheer hatred. Moskowitz had become convinced, and he remained so to his dying day,

that the Futurians had intended to cause trouble at the convention. But they were

still told they could come in if they agreed to behave themselves. But just about

this time, a big pack of pamphlets had been discovered, which Moskowitz, Sykora, and

Taurasi considered to be communistic propaganda that would be used to disrupt the

convention. So six of the Futurians Wollheim, Michel, Kornbluth, Lowndes,

Gillespie, and Pohl were turned away at the door, banned from the convention.

Interestingly enough, one of the members of the Futurians who did get in was

David A. Kyle, who was the guy who had written and printed that pamphlet!

That whole controversy unfortunately

overshadowed everything else that happened at the convention. It was a fascinating

event, with many good speeches. There were about 200 people there, which was

considered at that time as fantastic. Forry Ackerman came in from California, as

did Ray Bradbury -- Ackerman had loaned Bradbury the money to ride the bus to New

York City, and Bradbury brought with him a bunch of illustrations by a friend of his

named Hannes Bok. He peddled them around New York, and Weird Tales liked

them. After that, Bok become a very famous Weird Tales artist. That whole controversy unfortunately

overshadowed everything else that happened at the convention. It was a fascinating

event, with many good speeches. There were about 200 people there, which was

considered at that time as fantastic. Forry Ackerman came in from California, as

did Ray Bradbury -- Ackerman had loaned Bradbury the money to ride the bus to New

York City, and Bradbury brought with him a bunch of illustrations by a friend of his

named Hannes Bok. He peddled them around New York, and Weird Tales liked

them. After that, Bok become a very famous Weird Tales artist.

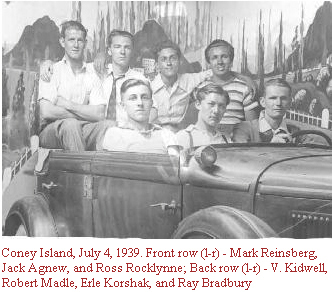

One of the most interesting events,

not part of the convention itself, was when a bunch of us, on July 4, 1939, went to

Coney Island. Ray Bradbury was with us, as was Jack Agnew, the writer Ross

Rocklynne, and also Mark Reinsberg, and Erle Korshak, who were in charge of the next

year's worldcon, in Chicago. We had a picture taken of us in one of those fake cars,

and it later showed up in many documents about science fiction fandom, including

The Immortal Storm. Ray Bradbury has a big blowup of that picture on the

wall of his basement. One of the most interesting events,

not part of the convention itself, was when a bunch of us, on July 4, 1939, went to

Coney Island. Ray Bradbury was with us, as was Jack Agnew, the writer Ross

Rocklynne, and also Mark Reinsberg, and Erle Korshak, who were in charge of the next

year's worldcon, in Chicago. We had a picture taken of us in one of those fake cars,

and it later showed up in many documents about science fiction fandom, including

The Immortal Storm. Ray Bradbury has a big blowup of that picture on the

wall of his basement.

We even had a softball game where the

Philadelphia club had challenged the New York fans, with Charles D. Hornig and Ray

Bradbury as score keep ers. Unfortunately, only about six of the Philadelphia guys

who played on the team showed up for the convention, so we had to pick up three or

four people. We were defeated, and we challenged them to a second game, but they

wouldn't play us again! We even had a softball game where the

Philadelphia club had challenged the New York fans, with Charles D. Hornig and Ray

Bradbury as score keep ers. Unfortunately, only about six of the Philadelphia guys

who played on the team showed up for the convention, so we had to pick up three or

four people. We were defeated, and we challenged them to a second game, but they

wouldn't play us again!

Another interesting thing that

happened at the world convention involved the Guest of Honor, Frank R. Paul. To

fans in those days, there was no other artist like Frank R. Paul; he personified

science fiction to all of us. I, Jack Agnew, Baltadonis, and Erle Korshak considered

him the greatest artist in the history of the world, and there he was, talking to

us. After we told him that, he said, "How would each of you boys like a free cover

illustration?" Another interesting thing that

happened at the world convention involved the Guest of Honor, Frank R. Paul. To

fans in those days, there was no other artist like Frank R. Paul; he personified

science fiction to all of us. I, Jack Agnew, Baltadonis, and Erle Korshak considered

him the greatest artist in the history of the world, and there he was, talking to

us. After we told him that, he said, "How would each of you boys like a free cover

illustration?"

We all said, "Sure!" We all said, "Sure!"

He wrote us a note, and said "Go on

in to see Mr. Gernsback tomorrow and give him this note. Tell him I said to give

each of you one of the covers." He wrote us a note, and said "Go on

in to see Mr. Gernsback tomorrow and give him this note. Tell him I said to give

each of you one of the covers."

So the next day we hopped on the

subway, and got over there and said, "We want to see Mr. Gernsback," and the next

thing we knew we were sitting and talking to Hugo Gernsback. We told him what Mr.

Paul had said, and gave him the note. Gernsback went into the back room, and a few

minutes he came back out and said, "Well, the owner of the covers says he has to get

$10 apiece for them." But that was an enormous amount of money back then; we had

just about enough money to be able to pay the nickel subway fare. One of the great

gods crumbled that day for us. So the next day we hopped on the

subway, and got over there and said, "We want to see Mr. Gernsback," and the next

thing we knew we were sitting and talking to Hugo Gernsback. We told him what Mr.

Paul had said, and gave him the note. Gernsback went into the back room, and a few

minutes he came back out and said, "Well, the owner of the covers says he has to get

$10 apiece for them." But that was an enormous amount of money back then; we had

just about enough money to be able to pay the nickel subway fare. One of the great

gods crumbled that day for us.

Anyway, except for the exclusion

incident, you'd have to grade that first worldcon as an 'A'. Much was written about

the convention in many, many fan magazines back then. Many people thought that

Moskowitz, Sykora, and Taurasi had made a big mistake, while others, such as Jack

Speer, agreed with them. I think history is still sorting it all out. Anyway, except for the exclusion

incident, you'd have to grade that first worldcon as an 'A'. Much was written about

the convention in many, many fan magazines back then. Many people thought that

Moskowitz, Sykora, and Taurasi had made a big mistake, while others, such as Jack

Speer, agreed with them. I think history is still sorting it all out.

The next worldcon, in 1940, was in

Chicago. New York fan Julius Unger had arranged to have somebody who was driving to

Chicago get us there -- all we had to do was buy some of the gasoline. Of course,

neither of knew how we were going to get back. I think I left home with five

dollars in my pocket my father had given me, which had broke him. The next worldcon, in 1940, was in

Chicago. New York fan Julius Unger had arranged to have somebody who was driving to

Chicago get us there -- all we had to do was buy some of the gasoline. Of course,

neither of knew how we were going to get back. I think I left home with five

dollars in my pocket my father had given me, which had broke him.

Like New York the year before, it was

also a great convention. Jerry Siegel was there, the creator of Superman.

The masquerades were created at the first Chicon; it had all started in 1939 when

Ackerman and his girlfriend Morojo showed up in New York dressed up in costumes from

Things to Come. Ackerman really started the idea of costumes at conventions.

At the Chicon, they actually encouraged you to have a costume, and they gave prizes

for them. Like New York the year before, it was

also a great convention. Jerry Siegel was there, the creator of Superman.

The masquerades were created at the first Chicon; it had all started in 1939 when

Ackerman and his girlfriend Morojo showed up in New York dressed up in costumes from

Things to Come. Ackerman really started the idea of costumes at conventions.

At the Chicon, they actually encouraged you to have a costume, and they gave prizes

for them.

The following year, in Denver, was

the smallest worldcon ever -- there were only about 90 people there. Lew Martin and

Olon Wiggins had ridden the rails in freight trains from Denver to the Chicago

worldcon; they decided, or maybe were talked into bidding for the next convention.

It seemed right that the worldcon was progressing ever westward, from New York to

Chicago, and then to Denver. The following year, in Denver, was

the smallest worldcon ever -- there were only about 90 people there. Lew Martin and

Olon Wiggins had ridden the rails in freight trains from Denver to the Chicago

worldcon; they decided, or maybe were talked into bidding for the next convention.

It seemed right that the worldcon was progressing ever westward, from New York to

Chicago, and then to Denver.

Back in 1941, it was like going to

the moon, going from Philadelphia to Denver. Art Widner and John Bell drove down

from Boston to get me, stopping in New York first to pick up Julie Unger. After

that, we went down to Washington, D.C., to get Milt Rothman, and then headed west.

On the way, we stopped briefly in Hagerstown, Maryland, to see Harry Warner, and

arrived very early the next morning in Bloomington, Illinois, to stay a day with

Bob Tucker. By then we were all so tired that when Tucker answered the door, we

crawled inside on our hands and knees. Later that day, Tucker brought Milt and me

down to the local draft board in Bloomington, where we registered. It caught the

attention of a reporter there that we were from out of town, so it got written up in

the local Bloomington newspaper. Back in 1941, it was like going to

the moon, going from Philadelphia to Denver. Art Widner and John Bell drove down

from Boston to get me, stopping in New York first to pick up Julie Unger. After

that, we went down to Washington, D.C., to get Milt Rothman, and then headed west.

On the way, we stopped briefly in Hagerstown, Maryland, to see Harry Warner, and

arrived very early the next morning in Bloomington, Illinois, to stay a day with

Bob Tucker. By then we were all so tired that when Tucker answered the door, we

crawled inside on our hands and knees. Later that day, Tucker brought Milt and me

down to the local draft board in Bloomington, where we registered. It caught the

attention of a reporter there that we were from out of town, so it got written up in

the local Bloomington newspaper.

Robert A. Heinlein was the Guest of

Honor at the Denver worldcon. Heinlein was a fairly new writer then; his first

story, "Life Line," had appeared in 1939. He was a fairly young chap, a former

Naval officer who had already been discharged for medical reasons. As it turned

out, there was a science fiction magazine called Comet Stories that was being

published by F. Orlin Tremaine, who had previously been the editor of Astounding

Stories until 1937 when John W. Campbell took over. Anyway, Tremaine had

previously announced there that he was giving an award of twenty-five dollars to the

fan who had "overcome the most obstacles" to get to the Denvention. (The winner was

somebody who had hitchhiked all the way there from Ohio.) But by the time the

convention occurred, Comet Stories had folded, so here was this prize that

somebody was supposed to get, and he wasn't getting it. So Heinlein got up and

announced that he would give the twenty-five dollars himself. It turned out that

Heinlein's birthday was right after the end of the convention, so we all chipped in,

50¢ apiece or something, and bought him about a dozen books his wife had told

us he would like to have. He was ecstatic! Robert A. Heinlein was the Guest of

Honor at the Denver worldcon. Heinlein was a fairly new writer then; his first

story, "Life Line," had appeared in 1939. He was a fairly young chap, a former

Naval officer who had already been discharged for medical reasons. As it turned

out, there was a science fiction magazine called Comet Stories that was being

published by F. Orlin Tremaine, who had previously been the editor of Astounding

Stories until 1937 when John W. Campbell took over. Anyway, Tremaine had

previously announced there that he was giving an award of twenty-five dollars to the

fan who had "overcome the most obstacles" to get to the Denvention. (The winner was

somebody who had hitchhiked all the way there from Ohio.) But by the time the

convention occurred, Comet Stories had folded, so here was this prize that

somebody was supposed to get, and he wasn't getting it. So Heinlein got up and

announced that he would give the twenty-five dollars himself. It turned out that

Heinlein's birthday was right after the end of the convention, so we all chipped in,

50¢ apiece or something, and bought him about a dozen books his wife had told

us he would like to have. He was ecstatic!

And then came World War II. Los

Angeles had been selected to host the 1942 Worldcon, but the War changed those plans

-- the huge majority of everybody who was in fandom went into the military service.

There were a few people who didn't go; the only one from Philadelphia who hadn't

gone into the military was Ossie Train, who kept in touch with others in Philadelphia

fandom by publishing PSFS News and sending it out to everybody who was in

the service. Only one of our members, Harvey Greenblatt, was killed during the War,

and he had been active enough before the War where you have to wonder what he might

have done if he had lived. And then came World War II. Los

Angeles had been selected to host the 1942 Worldcon, but the War changed those plans

-- the huge majority of everybody who was in fandom went into the military service.

There were a few people who didn't go; the only one from Philadelphia who hadn't

gone into the military was Ossie Train, who kept in touch with others in Philadelphia

fandom by publishing PSFS News and sending it out to everybody who was in

the service. Only one of our members, Harvey Greenblatt, was killed during the War,

and he had been active enough before the War where you have to wonder what he might

have done if he had lived.

After the war, the worldcons resumed.

I didn't go to the 1946 Los Angeles Worldcon, but Milton Rothman did. He bid for

Philadelphia for the 1947 convention, got it, and was elected the chairman when

he returned. The 1947 Worldcon you could say was the first adult convention -- the

first convention where beer and liquor liberally flowed. Right after the war several

small specialty publishers had gotten started -- Lloyd Esbach, of Fantasy Press,

Dave Kyle and Marty Greenberg with Gnome Press, and Tom Hadley with Hadley Publishing

Company. At the Philadelphia convention in 1947, each one had a big suite where

they would try to outdo each other with big parties, with beer and liquor. John

Campbell was the Guest of Honor; he had intended to come to Philadelphia only to

give his speech, and was going to leave after that. But he decided to hang around

for one of the parties, and he ended up staying for the whole convention. He had a

great time! After the war, the worldcons resumed.

I didn't go to the 1946 Los Angeles Worldcon, but Milton Rothman did. He bid for

Philadelphia for the 1947 convention, got it, and was elected the chairman when

he returned. The 1947 Worldcon you could say was the first adult convention -- the

first convention where beer and liquor liberally flowed. Right after the war several

small specialty publishers had gotten started -- Lloyd Esbach, of Fantasy Press,

Dave Kyle and Marty Greenberg with Gnome Press, and Tom Hadley with Hadley Publishing

Company. At the Philadelphia convention in 1947, each one had a big suite where

they would try to outdo each other with big parties, with beer and liquor. John

Campbell was the Guest of Honor; he had intended to come to Philadelphia only to

give his speech, and was going to leave after that. But he decided to hang around

for one of the parties, and he ended up staying for the whole convention. He had a

great time!

The concluding installment of this two-part article appears in

Mimosa 30.

The concluding installment of this two-part article appears in

Mimosa 30.

All illustrations by Charlie Williams

|