We don't normally publish articles

as long as this next one, but we couldn't resist Yugoslav fan Bruno Ogorelec's window

onto SF in Yugoslavia, past and present. We received it not more than a week before

we moved to Maryland; it's certainly the most unusual going-away present we've

ever gotten. We don't normally publish articles

as long as this next one, but we couldn't resist Yugoslav fan Bruno Ogorelec's window

onto SF in Yugoslavia, past and present. We received it not more than a week before

we moved to Maryland; it's certainly the most unusual going-away present we've

ever gotten.

- - - - - - - -

The history of American mass-market SF

and the fandom thereof -- from Gernsback till today via numerous pulpy begats -- has

been researched in exhaustive detail and seems to be familiar to everyone by now. The

British oldpharts, sharing most of the skiffy/fannish roots with their U.S. cousins,

have documented their own history just as painstakingly. They are much given to

recounting how they started reading SF after bumping into a cornucopia of American

pulp magazines, the lucky bastards. They were apparently imported in bulk (the pulps,

that is, not the lucky bastards) and sold for a pittance to the impressionable

British youngsters. No such luck for me, however, nor indeed for most of the other

Continental Europeans. The history of American mass-market SF

and the fandom thereof -- from Gernsback till today via numerous pulpy begats -- has

been researched in exhaustive detail and seems to be familiar to everyone by now. The

British oldpharts, sharing most of the skiffy/fannish roots with their U.S. cousins,

have documented their own history just as painstakingly. They are much given to

recounting how they started reading SF after bumping into a cornucopia of American

pulp magazines, the lucky bastards. They were apparently imported in bulk (the pulps,

that is, not the lucky bastards) and sold for a pittance to the impressionable

British youngsters. No such luck for me, however, nor indeed for most of the other

Continental Europeans.

Our lands have not been blessed with

such manna. Locally brewed science fiction pulps have always been rarer than hen's

milk here, while importing pulp magazines in a foreign language never made much sense,

of course. Even the early sixties (my entry point into fandom) were more or less a

barren desert. You Anglos had it easy. In the English-speaking countries there

existed a mass market for SF, and fandom flourished. It is a market phenomenon, after

all. Nowhere else could you find the skiffy-consuming masses for fandom to spring

from. It made significant inroads into the rest of the Western world only very

recently, with the advent of another mass market: media SF. Before that, non-Anglo

fandom was of necessity a realm of the unusual, of people like me, or worse. It has

always been sparse, its lot unsung and unresearched. Our lands have not been blessed with

such manna. Locally brewed science fiction pulps have always been rarer than hen's

milk here, while importing pulp magazines in a foreign language never made much sense,

of course. Even the early sixties (my entry point into fandom) were more or less a

barren desert. You Anglos had it easy. In the English-speaking countries there

existed a mass market for SF, and fandom flourished. It is a market phenomenon, after

all. Nowhere else could you find the skiffy-consuming masses for fandom to spring

from. It made significant inroads into the rest of the Western world only very

recently, with the advent of another mass market: media SF. Before that, non-Anglo

fandom was of necessity a realm of the unusual, of people like me, or worse. It has

always been sparse, its lot unsung and unresearched.

A pity, that. Most of us being

oddballs, we could have furnished some lurid fan histories. It takes a peculiar bent

of character to get this much involved in something you share with perhaps three or

four people in your entire country and which is, moreover, virtually unobtainable. A pity, that. Most of us being

oddballs, we could have furnished some lurid fan histories. It takes a peculiar bent

of character to get this much involved in something you share with perhaps three or

four people in your entire country and which is, moreover, virtually unobtainable.

In this vein, while we are on the

subject of unusual: a few months ago in Anvil, Skel wrote of an unusual Britfan

beginning -- to wit, getting his first SF book from his mother. It was a response to

Buck Coulson's column in an earlier issue in which Buck had stressed the improbability

of a fan's mother in the fifties having anything to do with anything as disrespectable

as science fiction. Hah! Piffle! If a mother was an improbable source of SF,

what about a grandmother? Or a great-grandmother? Now that is what I would

call improbable. In this vein, while we are on the

subject of unusual: a few months ago in Anvil, Skel wrote of an unusual Britfan

beginning -- to wit, getting his first SF book from his mother. It was a response to

Buck Coulson's column in an earlier issue in which Buck had stressed the improbability

of a fan's mother in the fifties having anything to do with anything as disrespectable

as science fiction. Hah! Piffle! If a mother was an improbable source of SF,

what about a grandmother? Or a great-grandmother? Now that is what I would

call improbable.

Yes, you guessed it, of course --

therein hangs a tale. A long one; I am congenitally incapable of writing anything

short and succinct: Yes, you guessed it, of course --

therein hangs a tale. A long one; I am congenitally incapable of writing anything

short and succinct:

Great Jumping Grandmothers

A Cautionary Tale of Female Emancipation

by Bruno Ogorelec

by Bruno Ogorelec

I am a scion of a venerable fannish

family whose passion for SF and fantasy started at about the same time the peace

accords were being hammered out at Versailles, in the aftermath of World War I.

My country, Yugoslavia, had just been put together out of assorted Balkan states,

nations, and territories. My family, in contrast, started going asunder. Did I say

"family"? Hm, for the want of a better word, perhaps. Well, you'll see for

yourself. I am a scion of a venerable fannish

family whose passion for SF and fantasy started at about the same time the peace

accords were being hammered out at Versailles, in the aftermath of World War I.

My country, Yugoslavia, had just been put together out of assorted Balkan states,

nations, and territories. My family, in contrast, started going asunder. Did I say

"family"? Hm, for the want of a better word, perhaps. Well, you'll see for

yourself.

If I want to begin at the beginning, I

must start with my great-grandmother. She discovered science fiction in 1920. It

wasn't labelled "science fiction", of course, but that's what it was. An awkward

person, my great-grandmother. Wish I could speak of her in a more positive light, her

being the very first fan of us all, etc., but by all accounts she was a difficult

woman; cold, rude, and fiercely independent. If I want to begin at the beginning, I

must start with my great-grandmother. She discovered science fiction in 1920. It

wasn't labelled "science fiction", of course, but that's what it was. An awkward

person, my great-grandmother. Wish I could speak of her in a more positive light, her

being the very first fan of us all, etc., but by all accounts she was a difficult

woman; cold, rude, and fiercely independent.

She married halfheartedly, only because

the changing social climate had made our comfortable family traditions no longer

acceptable. Till then, my female ancestors never even thought of getting married.

Instead, they occupied a rather peculiar niche in the contemporary order of things.

This will sound weird, I know, and have to brace myself for some incredulity; our

women were all illegitimate daughters of Catholic priests. When they grew up, they in

turn became women-about-church and the priests' concubines -- and eventually bore the

priests' illigetimate children. This is what we had in place of the conventional

family. (In the XIX century, mind you.) She married halfheartedly, only because

the changing social climate had made our comfortable family traditions no longer

acceptable. Till then, my female ancestors never even thought of getting married.

Instead, they occupied a rather peculiar niche in the contemporary order of things.

This will sound weird, I know, and have to brace myself for some incredulity; our

women were all illegitimate daughters of Catholic priests. When they grew up, they in

turn became women-about-church and the priests' concubines -- and eventually bore the

priests' illigetimate children. This is what we had in place of the conventional

family. (In the XIX century, mind you.)

It may seem like a mean existence to

you, but was in fact a pleasant enough life, vastly preferable to the fate of a

peasant's wife, for instance. The priests -- often highly-placed church officials --

took very good care of their women and children, making sure their "families" never

lacked anything. The women never had to toil for subsistence, a rare blessing in an

era in which a woman's toil was a terrible burden indeed. Work around the church was

undemanding and often interesting. Our women were educated far above the norm for

those days, and even had access to the church libraries. Their lives were simple,

easy, enlightened -- and independent, free of many stifling family strictures. No

wonder none of them ever wanted anything better either for themselves or for their

daughters. (For once it was the men who got the rough end of the arrangement. Sons

did not fit into the scene at all, and most of them drifted away and became itinerant

field hands.) It may seem like a mean existence to

you, but was in fact a pleasant enough life, vastly preferable to the fate of a

peasant's wife, for instance. The priests -- often highly-placed church officials --

took very good care of their women and children, making sure their "families" never

lacked anything. The women never had to toil for subsistence, a rare blessing in an

era in which a woman's toil was a terrible burden indeed. Work around the church was

undemanding and often interesting. Our women were educated far above the norm for

those days, and even had access to the church libraries. Their lives were simple,

easy, enlightened -- and independent, free of many stifling family strictures. No

wonder none of them ever wanted anything better either for themselves or for their

daughters. (For once it was the men who got the rough end of the arrangement. Sons

did not fit into the scene at all, and most of them drifted away and became itinerant

field hands.)

It was only my great-grandmother that

broke the tradition, pressured by the increasingly secular society, but according to

the family sources she did it reluctantly and later came to regret her bold move.

Before her time, scoffing at a cozy role in life such as hers was rare and pointless;

envy was a much more common reaction. However, with the decline of the feudal system

and the rise of urban democratic society, the church lost much of its clout and

prestige. The cachet of being a prelate's concubine had paled accordingly. It was only my great-grandmother that

broke the tradition, pressured by the increasingly secular society, but according to

the family sources she did it reluctantly and later came to regret her bold move.

Before her time, scoffing at a cozy role in life such as hers was rare and pointless;

envy was a much more common reaction. However, with the decline of the feudal system

and the rise of urban democratic society, the church lost much of its clout and

prestige. The cachet of being a prelate's concubine had paled accordingly.

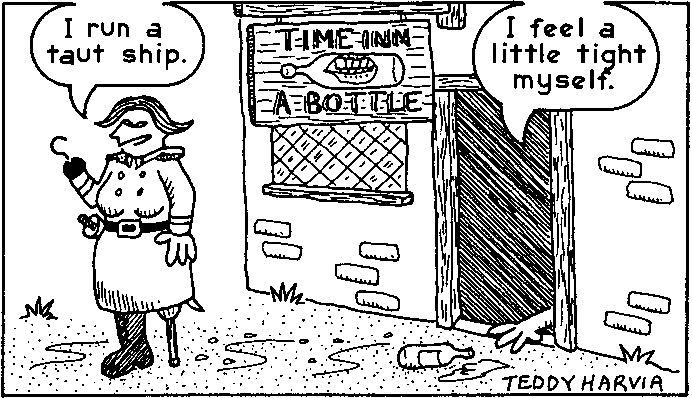

Great-grandma was a proud woman and

didn't want to be scoffed at. She ditched the tradition, married a young railroad

track inspector, and with the considerable family savings opened an inn in the

country. She ran a taut ship, gave good value for money to the inn's patrons, and

prospered. As a wife and mother, however, she was a failure, obviously resenting

having to take care of a household and family on top of her busy inn.

Great-granddad was thus happy to roam the country inspecting the railroad tracks,

returning home for one weekend a month (if that much). His wife of formidable will,

unsettling education, and unpleasant moods had turned out to be more than he could

handle, and it was good to be out of the way most of the time. Great-grandma was a proud woman and

didn't want to be scoffed at. She ditched the tradition, married a young railroad

track inspector, and with the considerable family savings opened an inn in the

country. She ran a taut ship, gave good value for money to the inn's patrons, and

prospered. As a wife and mother, however, she was a failure, obviously resenting

having to take care of a household and family on top of her busy inn.

Great-granddad was thus happy to roam the country inspecting the railroad tracks,

returning home for one weekend a month (if that much). His wife of formidable will,

unsettling education, and unpleasant moods had turned out to be more than he could

handle, and it was good to be out of the way most of the time.

Little Grandma, his daughter, soon

realized her Daddy hadn't been a fool. She was a teenager then and, though scarcely

involved in any momentous events, could clearly sense that big changes were afoot in

the wide world. She was seriously rethinking her options in life. At home she was

largely ignored as a person, but very much taken into account as a laborer. How

could she fancy being a waitress and kitchen helper in a country inn? She didn't

relish playing second fiddle to her mother's ego, either. As well educated as was the

family custom, she wanted more out of life. A whole new world beckoned her from

outside. So one day she simply packed her modest possessions and left for the Big

City. Little Grandma, his daughter, soon

realized her Daddy hadn't been a fool. She was a teenager then and, though scarcely

involved in any momentous events, could clearly sense that big changes were afoot in

the wide world. She was seriously rethinking her options in life. At home she was

largely ignored as a person, but very much taken into account as a laborer. How

could she fancy being a waitress and kitchen helper in a country inn? She didn't

relish playing second fiddle to her mother's ego, either. As well educated as was the

family custom, she wanted more out of life. A whole new world beckoned her from

outside. So one day she simply packed her modest possessions and left for the Big

City.

This is where we come back to science

fiction. Among the first possessions she packed were books. Perhaps a dozen

altogether, the cream of the cream of the family library. Among them were the two

freshest additions and Great-grandma's favorites: The End of the World and

The Last Days of Men by Camille Flammarion. Beautiful books bound in silky

green fabric, with titles embossed in black and gold. I remember them so vividly --

the smooth solid things with intricate ridges of the embossing, cool and pleasant to

touch, not like the modern slick book jackets that turn sticky against your palms. This is where we come back to science

fiction. Among the first possessions she packed were books. Perhaps a dozen

altogether, the cream of the cream of the family library. Among them were the two

freshest additions and Great-grandma's favorites: The End of the World and

The Last Days of Men by Camille Flammarion. Beautiful books bound in silky

green fabric, with titles embossed in black and gold. I remember them so vividly --

the smooth solid things with intricate ridges of the embossing, cool and pleasant to

touch, not like the modern slick book jackets that turn sticky against your palms.

They were all illustrated with superb,

richly lithographs of dark, brooding character, ideally complementing Flammarion's

literary images of decadence before the doom. The one I remember best depicted a rich

man's living room somewhere in Paris. He is reclining on an opulent sofa and watches a

huge flat circular TV screen, wall mounted in a baroque frame, with more levers

sprouting from its base than from a DC-3 control panel. The screen shows a plump

bejeweled belly dancer clad in silk dimi, performing before an audience of beggars and

street urchins somewhere in Baghdad. Another picture, much smaller, more of a

vignette, showed a cluster of badly misshapen flowers, ominous signs of the impending

fall. All pictures had fitting captions, dripping with morals, but they elude me

now. They were all illustrated with superb,

richly lithographs of dark, brooding character, ideally complementing Flammarion's

literary images of decadence before the doom. The one I remember best depicted a rich

man's living room somewhere in Paris. He is reclining on an opulent sofa and watches a

huge flat circular TV screen, wall mounted in a baroque frame, with more levers

sprouting from its base than from a DC-3 control panel. The screen shows a plump

bejeweled belly dancer clad in silk dimi, performing before an audience of beggars and

street urchins somewhere in Baghdad. Another picture, much smaller, more of a

vignette, showed a cluster of badly misshapen flowers, ominous signs of the impending

fall. All pictures had fitting captions, dripping with morals, but they elude me

now.

Great grandmother was furious at her

daughter's flight. Amazingly, it was the "theft" of books that incensed her the most.

To her the books were a bit sacred, a link to her rather elevated past, and a token of

her stature in the community. The only other people in the village that read books

were the parish priest and the school teacher. Flammarion's disappearance pained her

most acutely. She clearly loved the fantastic literature, her latest discovery, best

of all. It was a genre much frowned upon by the church then and reading it was thus a

small defiant gesture towards the regrettably abandoned curia. Small, because

Flammarion was a religious moralist at heart. Flaunting him was at best a hedged bet.

(Curiously enough, the church libraries routinely held books that were not

Ideologically Sound, even while railing against them in public. But then, laymen

generally did not have access to them, and the priests must have been considered

immune to their corrosive influence.) Great grandmother was furious at her

daughter's flight. Amazingly, it was the "theft" of books that incensed her the most.

To her the books were a bit sacred, a link to her rather elevated past, and a token of

her stature in the community. The only other people in the village that read books

were the parish priest and the school teacher. Flammarion's disappearance pained her

most acutely. She clearly loved the fantastic literature, her latest discovery, best

of all. It was a genre much frowned upon by the church then and reading it was thus a

small defiant gesture towards the regrettably abandoned curia. Small, because

Flammarion was a religious moralist at heart. Flaunting him was at best a hedged bet.

(Curiously enough, the church libraries routinely held books that were not

Ideologically Sound, even while railing against them in public. But then, laymen

generally did not have access to them, and the priests must have been considered

immune to their corrosive influence.)

Her daughter inherited this appreciation

of the fantastic, but went a step further, embracing "hard" SF as well. For her, free

of any longing for the staid tradition, Jules Verne was the man to watch, writing of

the brave new times and gadgets, and of men with the Right Stuff. Her daughter inherited this appreciation

of the fantastic, but went a step further, embracing "hard" SF as well. For her, free

of any longing for the staid tradition, Jules Verne was the man to watch, writing of

the brave new times and gadgets, and of men with the Right Stuff.

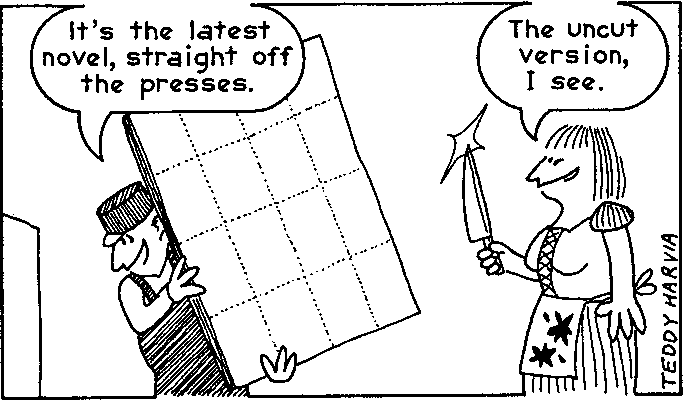

I have often wondered how she managed

to buy books. She came to Zagreb with a small cardboard suitcase, little money, and

fewer prospects for a sound and gainful employment. Luck was with her, though. She

soon found a job as a printer's assistant in the big Tipografija printing

plant which specialized in all kinds of office forms for the government, banks,

insurance companies, etc. It was hard work and paid little, while the books were

frightfully expensive. Common fold hardly ever read real books -- but then, Grandma

had always considered herself a cut above common, inheriting from her mother also a

dose of haughtiness. Ordinary literate people found their reading pleasure in, well,

pulps. Not SF, I hasten to say, but historical romances and novels of intrigue.

They were more basic than American pulps, insofar as they didn't have proper covers

and weren't even bound or cut. The big printer sheet (46" x 33") was simply folded

over four times to give 32 uncut pages. An illustration and a title were printed in

the corner destined to end up as the front page, and that was it. You would cut the

pages yourself, most often with a kitchen knife, and perhaps sew the pages together at

a fold with a sewing needle and some thread. I don't think staples existed then. If

there were any around they must have been out of common folk's reach. I have often wondered how she managed

to buy books. She came to Zagreb with a small cardboard suitcase, little money, and

fewer prospects for a sound and gainful employment. Luck was with her, though. She

soon found a job as a printer's assistant in the big Tipografija printing

plant which specialized in all kinds of office forms for the government, banks,

insurance companies, etc. It was hard work and paid little, while the books were

frightfully expensive. Common fold hardly ever read real books -- but then, Grandma

had always considered herself a cut above common, inheriting from her mother also a

dose of haughtiness. Ordinary literate people found their reading pleasure in, well,

pulps. Not SF, I hasten to say, but historical romances and novels of intrigue.

They were more basic than American pulps, insofar as they didn't have proper covers

and weren't even bound or cut. The big printer sheet (46" x 33") was simply folded

over four times to give 32 uncut pages. An illustration and a title were printed in

the corner destined to end up as the front page, and that was it. You would cut the

pages yourself, most often with a kitchen knife, and perhaps sew the pages together at

a fold with a sewing needle and some thread. I don't think staples existed then. If

there were any around they must have been out of common folk's reach.

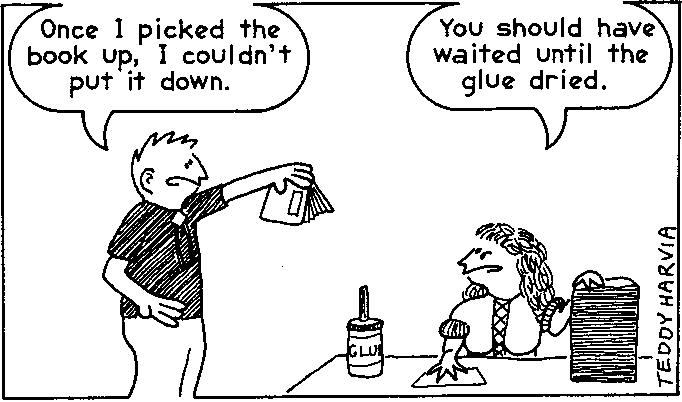

While Grandma did prefer (and buy)

books, the pulps were certainly not below notice in her household. They were purchased

regularly, read carefully, and then bound together in volumes. She befriended some

guys in the printing shop bindery, bribed them with beer and smiles and got proper

hard bindings done. As the Tipografija works only did office supplies and thus

only had relevant binding materials, Granny's bookshelf looked suspiciously like an

office file cabinet, with rows of what looked like stiff cardboard file dossiers, dark

gray with a pattern of dark green swirls, edged with black cloth and labelled along the

spine. The labels were blank, though, and once you took a "file dossier" down from the

shelf you saw the illustrated front page of the pulp romance neatly cut, glued, and

pressed onto the front side. Rather like those fake-bookshelf cocktail cabinets, only

in reverse. While Grandma did prefer (and buy)

books, the pulps were certainly not below notice in her household. They were purchased

regularly, read carefully, and then bound together in volumes. She befriended some

guys in the printing shop bindery, bribed them with beer and smiles and got proper

hard bindings done. As the Tipografija works only did office supplies and thus

only had relevant binding materials, Granny's bookshelf looked suspiciously like an

office file cabinet, with rows of what looked like stiff cardboard file dossiers, dark

gray with a pattern of dark green swirls, edged with black cloth and labelled along the

spine. The labels were blank, though, and once you took a "file dossier" down from the

shelf you saw the illustrated front page of the pulp romance neatly cut, glued, and

pressed onto the front side. Rather like those fake-bookshelf cocktail cabinets, only

in reverse.

But below the bound pulps were shelves

of real books. A surprising number of them were fantasy or science fiction,

considering how few had been published here at all by that time. The French had a

notable presence, far bigger than they would manage (or merit) nowadays. Jules Verne

led the pack, naturally, but his lead would have been even greater had Grandma ever

learned the Cyrillic alphabet. Several interesting SF books had been published in

Belgrade in Cyrillic, among them the first SF book ever published in these parts:

Jules Verne's A Journey to the Centre of the Earth in 1873 (only six years

after the Turkish army had retreated from Belgrade, freeing it after 450 years of

Ottoman occupation!). But below the bound pulps were shelves

of real books. A surprising number of them were fantasy or science fiction,

considering how few had been published here at all by that time. The French had a

notable presence, far bigger than they would manage (or merit) nowadays. Jules Verne

led the pack, naturally, but his lead would have been even greater had Grandma ever

learned the Cyrillic alphabet. Several interesting SF books had been published in

Belgrade in Cyrillic, among them the first SF book ever published in these parts:

Jules Verne's A Journey to the Centre of the Earth in 1873 (only six years

after the Turkish army had retreated from Belgrade, freeing it after 450 years of

Ottoman occupation!).

Of Wells there was only The Invisible

Man; surprising in view of Granny's strong Socialist leanings. It was a 1914

edition with no illustrations, which was quite unusual for the time. Perhaps the

illustrator found drawing an invisible hero too much of a challenge? The only other

English title, as far as I can remember, was Bellamy's Looking Backward... No

E.A. Poe, who was virtually unknown here till the fifties for some unfathomable

reason. No Stapledon, either. But then, Olaf Stapledon still hasn't been published

here at all... Of Wells there was only The Invisible

Man; surprising in view of Granny's strong Socialist leanings. It was a 1914

edition with no illustrations, which was quite unusual for the time. Perhaps the

illustrator found drawing an invisible hero too much of a challenge? The only other

English title, as far as I can remember, was Bellamy's Looking Backward... No

E.A. Poe, who was virtually unknown here till the fifties for some unfathomable

reason. No Stapledon, either. But then, Olaf Stapledon still hasn't been published

here at all...

Despite long hours and miserly pay,

Grandma did manage to buy and read books and indulge in some other soul-satisfying

activities, like singing. In her time off she sang in the trade union choir, and

there she met my grandfather, her husband. He sang in the Print & Graphic Trades

Union Choir despite being a panel beater. The contemporary repertory apparently put

a heavy emphasis on lyrical tenors and Grandpa, a carouser of some repute, was also

reputed to have a voice of a macho nightingale. The PGTU choirmaster had lured him

away from the Machinist's Union Choir offering him God knows what, but most

probably the chance to sing with girls (the MU Choir was, not surprisingly,

all male). Grandpa took the opportunity with both hands. In the new crowd he soon

found a good companion in my grandmother, who also liked singing, wine, and merry

company, and they got happily married. Despite long hours and miserly pay,

Grandma did manage to buy and read books and indulge in some other soul-satisfying

activities, like singing. In her time off she sang in the trade union choir, and

there she met my grandfather, her husband. He sang in the Print & Graphic Trades

Union Choir despite being a panel beater. The contemporary repertory apparently put

a heavy emphasis on lyrical tenors and Grandpa, a carouser of some repute, was also

reputed to have a voice of a macho nightingale. The PGTU choirmaster had lured him

away from the Machinist's Union Choir offering him God knows what, but most

probably the chance to sing with girls (the MU Choir was, not surprisingly,

all male). Grandpa took the opportunity with both hands. In the new crowd he soon

found a good companion in my grandmother, who also liked singing, wine, and merry

company, and they got happily married.

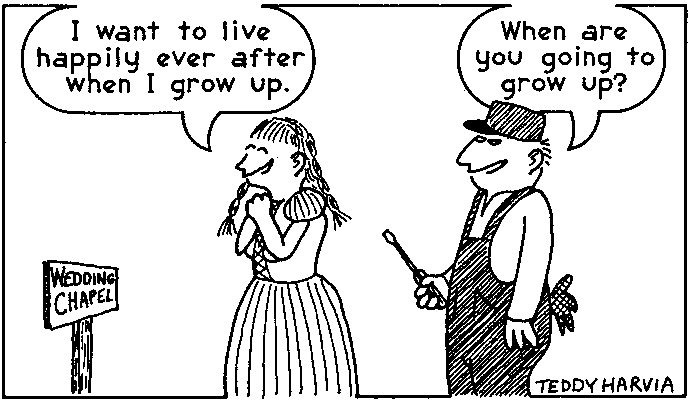

But they did not live happily ever

after, alas. A sad note intrudes here. Grandma soon lost her job. She was very

active in the PGTU, helped organize a big strike in the late twenties and got sacked

in the Tipografija owners' reprisals. For two years the Trade Union Strike

Fund paid her a weekly allowance, but with the onset of the Great Depression their

coffers dried up. By that time, the daughters had arrived, three of them in quick

succession, the one in the middle being my mother. Grandpa fell ill, suddenly. A

stomach cancer was diagnosed; very soon he withered away and died. But they did not live happily ever

after, alas. A sad note intrudes here. Grandma soon lost her job. She was very

active in the PGTU, helped organize a big strike in the late twenties and got sacked

in the Tipografija owners' reprisals. For two years the Trade Union Strike

Fund paid her a weekly allowance, but with the onset of the Great Depression their

coffers dried up. By that time, the daughters had arrived, three of them in quick

succession, the one in the middle being my mother. Grandpa fell ill, suddenly. A

stomach cancer was diagnosed; very soon he withered away and died.

But the women in my family have

titanium-alloy backbones. They know not defeat. But the women in my family have

titanium-alloy backbones. They know not defeat.

The legend has it that one day, as

Grandpa lay ill on a cot in the kitchen -- to be at Grandma's hand in case he needed

anything -- the taxman came to the door to collect long-overdue taxes. He'd come armed

with a court order empowering him to seize moveable property in case the tax debt could

not be collected in cash or financial paper. Grandma herself used to recount the

thunderous encounter with some relish, cackling gleefully. When the appeals failed to

soften the taxman's resolve, she went over to the woodshed and returned with a huge

axe, a mean four-foot mother she could barely raise with both hands, and offered to

split his skull if he dared to cross the threshold. The funny and mysterious thing is

that, after beating a hasty retreat, he never came back, ever. Grandma has always

maintained that she never paid those back taxes, and that nobody has ever tried to

collect them again. The legend has it that one day, as

Grandpa lay ill on a cot in the kitchen -- to be at Grandma's hand in case he needed

anything -- the taxman came to the door to collect long-overdue taxes. He'd come armed

with a court order empowering him to seize moveable property in case the tax debt could

not be collected in cash or financial paper. Grandma herself used to recount the

thunderous encounter with some relish, cackling gleefully. When the appeals failed to

soften the taxman's resolve, she went over to the woodshed and returned with a huge

axe, a mean four-foot mother she could barely raise with both hands, and offered to

split his skull if he dared to cross the threshold. The funny and mysterious thing is

that, after beating a hasty retreat, he never came back, ever. Grandma has always

maintained that she never paid those back taxes, and that nobody has ever tried to

collect them again.

If she was capable of putting the fear

of God into the Municipal Revenue Services, she certainly wasn't going to be fazed by

life's minor knocks, so she somehow raised her three daughters single-handedly,

despite the highly irregular income, and by my mother's words, she did it with flair

and in style. The girls were fine-mannered and always well-dressed. Grandma had even

offered them good education, but all three stopped after high school and found jobs

instead. If she was capable of putting the fear

of God into the Municipal Revenue Services, she certainly wasn't going to be fazed by

life's minor knocks, so she somehow raised her three daughters single-handedly,

despite the highly irregular income, and by my mother's words, she did it with flair

and in style. The girls were fine-mannered and always well-dressed. Grandma had even

offered them good education, but all three stopped after high school and found jobs

instead.

For some reason only my mother inherited

the literary interests of her idiosyncratic mother and grandmother, but that was

enough to keep the tradition. When she married and went to live with my father, she

started a SF library of her own and now has a sizeable collection, including, I think,

all SF books published in the Croatian/Serbian language after the war. She has always

felt that by embracing science fiction, she took over a family trust that had been

kept and nurtured over the generations. She still has this sense of mission, almost,

and could never really understand her sisters' total lack of interest. How could

anyone fail to see the innate conceptual beauty of science fiction was beyond

her powers of comprehension. For some reason only my mother inherited

the literary interests of her idiosyncratic mother and grandmother, but that was

enough to keep the tradition. When she married and went to live with my father, she

started a SF library of her own and now has a sizeable collection, including, I think,

all SF books published in the Croatian/Serbian language after the war. She has always

felt that by embracing science fiction, she took over a family trust that had been

kept and nurtured over the generations. She still has this sense of mission, almost,

and could never really understand her sisters' total lack of interest. How could

anyone fail to see the innate conceptual beauty of science fiction was beyond

her powers of comprehension.

This is the environment I grew up in,

you see. This is the environment I grew up in,

you see.

Funnily enough, the tradition has always

been handed down from mother to daughter, no men in my family ever having the slightest

interest in SF. Great-granddad never read anything at all, excepting the Agramer

Tagblatt, the leading Zagreb German-language daily paper in its day. Grandfather,

in turn, respected his wife's tastes but preferred the French classics and,

surprisingly, Grandma's bound pulp romances. My father, a physicist of international

repute, hates science fiction. Funnily enough, the tradition has always

been handed down from mother to daughter, no men in my family ever having the slightest

interest in SF. Great-granddad never read anything at all, excepting the Agramer

Tagblatt, the leading Zagreb German-language daily paper in its day. Grandfather,

in turn, respected his wife's tastes but preferred the French classics and,

surprisingly, Grandma's bound pulp romances. My father, a physicist of international

repute, hates science fiction.

So there it was -- the beginning of the

sixties, the Hula Hoop craze had already subsided, Rock'n'Roll had started its

conquest of the Balkans, and there was still no female offspring in sight to take the

tradition over. Bene Gesserit were getting worried. Was the work and dedication of

generations destined to turn into dust, with no one to carry the torch? Grandma,

distracted by life's calamities, had managed to instill the True Faith in just one of

her three daughters and that one, perversely, bore her a grandson, not a

granddaughter. Useless. You couldn't make a man into a Truthsayer. Family history

had by that time proved conclusively that men simply did not take to science fiction.

The other two daughters did have female offspring but the young girls couldn't be

bothered to peruse the comics, much less read the weightier stuff like Heinlein's

juveniles or Isaac Asimov. To all appearances it was a dead end. So there it was -- the beginning of the

sixties, the Hula Hoop craze had already subsided, Rock'n'Roll had started its

conquest of the Balkans, and there was still no female offspring in sight to take the

tradition over. Bene Gesserit were getting worried. Was the work and dedication of

generations destined to turn into dust, with no one to carry the torch? Grandma,

distracted by life's calamities, had managed to instill the True Faith in just one of

her three daughters and that one, perversely, bore her a grandson, not a

granddaughter. Useless. You couldn't make a man into a Truthsayer. Family history

had by that time proved conclusively that men simply did not take to science fiction.

The other two daughters did have female offspring but the young girls couldn't be

bothered to peruse the comics, much less read the weightier stuff like Heinlein's

juveniles or Isaac Asimov. To all appearances it was a dead end.

But appearances can be deceiving, you

know. But appearances can be deceiving, you

know.

It was a fine summer day in Zagreb.

Mother was cooking dinner, her son destroying the last of the cherry pie, browsing

through some old issues of Savremena Tehnika (a kind of local Popular

Mechanics), and all was well with the world. It was a fine summer day in Zagreb.

Mother was cooking dinner, her son destroying the last of the cherry pie, browsing

through some old issues of Savremena Tehnika (a kind of local Popular

Mechanics), and all was well with the world.

"Mom!" the boy called out. "How does a

mountain open?" "Mom!" the boy called out. "How does a

mountain open?"

"What?" "What?"

"How does a mountain open?" "How does a mountain open?"

"Hm. Well, it doesn't, usually." "Hm. Well, it doesn't, usually."

"Yes, it does. It says so here.

Listen: 'When it looked as if our flying machine would crash straight into the

mountainside, the huge rock face simply split apart. The entire mountain opened along

a vertical seam. Full speed ahead, we flew through the opening and into a giant

brightly-lit cavern cut into the rock. Already the mountain was closing back behind

us like a clamshell, cutting us off from the red desert and orange sky. We were inside

Mars!'" "Yes, it does. It says so here.

Listen: 'When it looked as if our flying machine would crash straight into the

mountainside, the huge rock face simply split apart. The entire mountain opened along

a vertical seam. Full speed ahead, we flew through the opening and into a giant

brightly-lit cavern cut into the rock. Already the mountain was closing back behind

us like a clamshell, cutting us off from the red desert and orange sky. We were inside

Mars!'"

Mom dropped her pots and pans in shock,

her face blanched. She couldn't believe her ears. With the tympans pounding Richard

Strauss' "Zarathustra" in her mind she ran over to the boy and looked at the magazine

in his hands. Aye, there it was, verily, the third installment of Among the

Martians, a short novel by Hugo Gernsback. Mom dropped her pots and pans in shock,

her face blanched. She couldn't believe her ears. With the tympans pounding Richard

Strauss' "Zarathustra" in her mind she ran over to the boy and looked at the magazine

in his hands. Aye, there it was, verily, the third installment of Among the

Martians, a short novel by Hugo Gernsback.

A curious sound escaped her lips,

neither a shout nor a whisper. To the boy it sounded like a name, a man's name in some

strange and exotic language: Kwisatz Haderach! But it could have been just a

sneeze. A curious sound escaped her lips,

neither a shout nor a whisper. To the boy it sounded like a name, a man's name in some

strange and exotic language: Kwisatz Haderach! But it could have been just a

sneeze.

At any rate, the boy took to science

fiction like a duck to the water, to the disbelief of the women. He thrived on the

skiffy diet, growing and growing in stature and fannishness over the years, finally

to become me as I am today, a worthy successor to the science fiction witch

coven. Unexpectedly, I even found the place that no Truthsayer could see into. It

was said that "... a man would come one day and find ... his inward eye, and that he

would look where Truthsayers before him couldn't." At any rate, the boy took to science

fiction like a duck to the water, to the disbelief of the women. He thrived on the

skiffy diet, growing and growing in stature and fannishness over the years, finally

to become me as I am today, a worthy successor to the science fiction witch

coven. Unexpectedly, I even found the place that no Truthsayer could see into. It

was said that "... a man would come one day and find ... his inward eye, and that he

would look where Truthsayers before him couldn't."

I found that place in the English

language. I found that place in the English

language.

Before me, no one in the family ever

learned English; German and Hungarian were our foreign languages of choice. All

foreign science fiction we read had been translated. Roughly a third of it was

Russian, another third French, and the rest Angloamerican. The others were truly

rare. The rarest of all were the Yugoslav authors, a mere dozen or so. It was a fine,

if limited, choice. To an American fan it would be quite unfamiliar, the Russian part

in particular. More's the pity. Before me, no one in the family ever

learned English; German and Hungarian were our foreign languages of choice. All

foreign science fiction we read had been translated. Roughly a third of it was

Russian, another third French, and the rest Angloamerican. The others were truly

rare. The rarest of all were the Yugoslav authors, a mere dozen or so. It was a fine,

if limited, choice. To an American fan it would be quite unfamiliar, the Russian part

in particular. More's the pity.

I liked the Russian stuff pretty much

most of the time. Alexander Belyayev used to be a favorite, the grand old man of

Russian SF, bound to the wheelchair by polio and compensating for the sedentary

destiny in a spectacular manner, inventing very lifelike and convincing heroes:

amphibious men, flying men, and mad scientists. To me, the fondest of his creations,

however, is a certain young lady from "The Head of Professor Dowell", written in the

late forties. The said professor had an unusual dream: to salvage from crash victims

what body parts were in viable condition, and recycle them. Out of the remains of two

or three deaders he would cobble together one live one, reducing thereby the traffic

fatalities tally by thirty to fifty percent -- a noble aim in the forties, surely.

Totally impractical now, of course, what with the current cost of malpractice

insurance and all. Anyway, he kept the heads potted, somewhat like petunias, in the

basement lab and fed them hydroponically. One head used to belong to a lovely, shy,

fragile blonde. Very conveniently, along comes a delectable corpse of a hot-blooded

bar singer, shot through the forehead by a jealous lover. The voluptuous body is mated

to the elfin head, and the results are hilarious as the worldly body clashes with a

shy and innocent mind. A good book. I liked the Russian stuff pretty much

most of the time. Alexander Belyayev used to be a favorite, the grand old man of

Russian SF, bound to the wheelchair by polio and compensating for the sedentary

destiny in a spectacular manner, inventing very lifelike and convincing heroes:

amphibious men, flying men, and mad scientists. To me, the fondest of his creations,

however, is a certain young lady from "The Head of Professor Dowell", written in the

late forties. The said professor had an unusual dream: to salvage from crash victims

what body parts were in viable condition, and recycle them. Out of the remains of two

or three deaders he would cobble together one live one, reducing thereby the traffic

fatalities tally by thirty to fifty percent -- a noble aim in the forties, surely.

Totally impractical now, of course, what with the current cost of malpractice

insurance and all. Anyway, he kept the heads potted, somewhat like petunias, in the

basement lab and fed them hydroponically. One head used to belong to a lovely, shy,

fragile blonde. Very conveniently, along comes a delectable corpse of a hot-blooded

bar singer, shot through the forehead by a jealous lover. The voluptuous body is mated

to the elfin head, and the results are hilarious as the worldly body clashes with a

shy and innocent mind. A good book.

Modern Angloamerican science fiction

was represented by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, and hardly anyone

else. The others appeared haphazardly, by accident more than by design. We had no

reason to suppose that Angloamerican SF was more plentiful than French SF. It was

more exciting, true, but contemporary Russian SF often matched it in excitement and

was usually better written. Of the Americans we knew, only Bradbury could write but

his SF was wooly and poetic, which was counted against him. Way back then we still

expected science fiction to have some hair on its chest. Modern Angloamerican science fiction

was represented by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, and hardly anyone

else. The others appeared haphazardly, by accident more than by design. We had no

reason to suppose that Angloamerican SF was more plentiful than French SF. It was

more exciting, true, but contemporary Russian SF often matched it in excitement and

was usually better written. Of the Americans we knew, only Bradbury could write but

his SF was wooly and poetic, which was counted against him. Way back then we still

expected science fiction to have some hair on its chest.

Ahem. Where was I? Ah, yes; the

English language. I learned it as a lark, mostly. Some of my friends collected

stamps, the others made model aeroplanes, and I collected feelthy peekchers and studied

English. Frankly, it wasn't of much practical use to me. The English language, I

mean. Rock lyrics have always been unintelligible, even to the native English

speakers. Movies were (and still are, thank God) subtitled. What else was there? Ahem. Where was I? Ah, yes; the

English language. I learned it as a lark, mostly. Some of my friends collected

stamps, the others made model aeroplanes, and I collected feelthy peekchers and studied

English. Frankly, it wasn't of much practical use to me. The English language, I

mean. Rock lyrics have always been unintelligible, even to the native English

speakers. Movies were (and still are, thank God) subtitled. What else was there?

Well, in time I found the British

motoring magazines. Ah, the Autocar, for example! The patrician among the

peasants. I didn't understand much at first, but it doesn't take you too long to

learn such pearly perfect syntagms 'The Double Overhead Camshaft' or 'Desmodromic

Valve Actuation'. Pure poetry in steel and Valvoline. Gradually I soaked up enough

of a vocabulary to read and understand most of the articles. I even learned that you

didn't say "bonnet" or "boot" to an American, but "hood" and "trunk" instead, and

that the tyres and tires were one and the same thing. Well, in time I found the British

motoring magazines. Ah, the Autocar, for example! The patrician among the

peasants. I didn't understand much at first, but it doesn't take you too long to

learn such pearly perfect syntagms 'The Double Overhead Camshaft' or 'Desmodromic

Valve Actuation'. Pure poetry in steel and Valvoline. Gradually I soaked up enough

of a vocabulary to read and understand most of the articles. I even learned that you

didn't say "bonnet" or "boot" to an American, but "hood" and "trunk" instead, and

that the tyres and tires were one and the same thing.

And then, inevitably, I bumped into

science fiction. And then, inevitably, I bumped into

science fiction.

By the mid-sixties I had read virtually

every single SF book available in Croatian/Serbian and was down to the misfiles --

you know, the books with promising but misleading titles (like Jack London's Moon

Valley) or non-SF books by SF authors. Logic said that there must have been some

misfiles in the opposite direction as well, science fiction that did not look like

science fiction. I started fine-combing the entire stock of a big public library to

find them, and Bingo! found one in the very first try. It was From Lucianus to

Lunik by Darko Suvin, filed -- not entirely unexpectedly -- under "Literary

Theory". It actually was literary theory, a hefty volume explaining science fiction,

that they snubbed it out of prejudice, not out of knowledge. So, to illustrate the

points he made, he had included a dozen SF stories in a kind of appendix. I opened

the book at the appendix and was hooked from the start. In the first entry even the

author's name dripped with the sense of wonder -- Cordwainer Smith! The story was

"Scanners Live in Vain" and it hit me like a sledgehammer. By the mid-sixties I had read virtually

every single SF book available in Croatian/Serbian and was down to the misfiles --

you know, the books with promising but misleading titles (like Jack London's Moon

Valley) or non-SF books by SF authors. Logic said that there must have been some

misfiles in the opposite direction as well, science fiction that did not look like

science fiction. I started fine-combing the entire stock of a big public library to

find them, and Bingo! found one in the very first try. It was From Lucianus to

Lunik by Darko Suvin, filed -- not entirely unexpectedly -- under "Literary

Theory". It actually was literary theory, a hefty volume explaining science fiction,

that they snubbed it out of prejudice, not out of knowledge. So, to illustrate the

points he made, he had included a dozen SF stories in a kind of appendix. I opened

the book at the appendix and was hooked from the start. In the first entry even the

author's name dripped with the sense of wonder -- Cordwainer Smith! The story was

"Scanners Live in Vain" and it hit me like a sledgehammer.

The book's theoretical part was no less

fascinating. It traced the history of fantastic literature all the way back to the

ancients, and analyzed its content to show the reasons for its enduring importance

in the human culture. Somehow I have always felt science fiction to be more important

than its surface showed, but could never quite frame the right arguments. All of a

sudden there was that professor in Zagreb who understood. The book's theoretical part was no less

fascinating. It traced the history of fantastic literature all the way back to the

ancients, and analyzed its content to show the reasons for its enduring importance

in the human culture. Somehow I have always felt science fiction to be more important

than its surface showed, but could never quite frame the right arguments. All of a

sudden there was that professor in Zagreb who understood.

He opened my eyes in yet another

respect, teaching me that somewhere out there, there existed an incredibly vast

mountain of science fiction in English, of which I had never even dreamt. That all the

SF I had read till then was but an anthill compared to the Himalayas. My mother also

read Suvin's book and was nonplussed. She liked the stories a lot (Heinlein's "Misfit"

being her favorite) but hated the idea of thousands of such stories, out of reach

because of the language barrier. She felt betrayed. He opened my eyes in yet another

respect, teaching me that somewhere out there, there existed an incredibly vast

mountain of science fiction in English, of which I had never even dreamt. That all the

SF I had read till then was but an anthill compared to the Himalayas. My mother also

read Suvin's book and was nonplussed. She liked the stories a lot (Heinlein's "Misfit"

being her favorite) but hated the idea of thousands of such stories, out of reach

because of the language barrier. She felt betrayed.

I felt feverish. God, could it be

true? I felt feverish. God, could it be

true?

From the age of five I'd been a member

of the library and yet I never climbed the short flight of stairs leading to the first

floor. There was no reason to -- it held the foreign language books. But now...

Suddenly I put two and two together and ran all the way to the library, three or

four miles, the tram seeing far too slow and roundabout for my purpose. From the age of five I'd been a member

of the library and yet I never climbed the short flight of stairs leading to the first

floor. There was no reason to -- it held the foreign language books. But now...

Suddenly I put two and two together and ran all the way to the library, three or

four miles, the tram seeing far too slow and roundabout for my purpose.

I will state publicly here that my

collision, head on, with the rows upon rows of science fiction paperbacks on the

library shelves stands as one of the two distinct pinnacles of excitement in all my

37 years of life. (The other was a fresh spring day a year or so earlier, when a

stunningly beautiful Jewish girl I tutored in geography invited me to get more

physical in my approach to learning. Sweet Jesus, what delights that girl had in

store!) I will state publicly here that my

collision, head on, with the rows upon rows of science fiction paperbacks on the

library shelves stands as one of the two distinct pinnacles of excitement in all my

37 years of life. (The other was a fresh spring day a year or so earlier, when a

stunningly beautiful Jewish girl I tutored in geography invited me to get more

physical in my approach to learning. Sweet Jesus, what delights that girl had in

store!)

But I was talking of science fiction,

wasn't I? I spent the entire afternoon in the library and was forcibly evicted at the

closing time, with two books chosen after hours of painful deliberation clutched in my

hands. One was Galaxies Like Grains of Dust by Brian Aldiss, and the other

The Reefs of Space, the first book of the Starchild trilogy by Fred Pohl and

Jack Williamson. Despite a very shaky command of English, I read them right through

at once, one through the night and the other next morning, every single word of them.

I would have read the bar codes, even, if they had been invented by then. But I was talking of science fiction,

wasn't I? I spent the entire afternoon in the library and was forcibly evicted at the

closing time, with two books chosen after hours of painful deliberation clutched in my

hands. One was Galaxies Like Grains of Dust by Brian Aldiss, and the other

The Reefs of Space, the first book of the Starchild trilogy by Fred Pohl and

Jack Williamson. Despite a very shaky command of English, I read them right through

at once, one through the night and the other next morning, every single word of them.

I would have read the bar codes, even, if they had been invented by then.

Thus started the final stage in my

transformation into a fan. One to two books a day for months and months on end, with

unceasing fervor and dedication. My great-grandmother must have smiled on me

benevolently from the Great Worldcon in the Sky where she went after giving up on the

mundane world at the age of 90. Grandmother did smile benevolently, even though

she apparently disbelieved the existence of so much SF in the world. Her disbelief was

abetted by the weird covers of my paperbacks; nothing that lurid could have been

serious, in her opinion. Mother did not smile benevolently; she was piqued. Only when

a flurry of small press publishers appeared here in the eighties and started flooding

the market with translated Angloamerican SF, did she forgive me for having the gall to

look where she could not. Thus started the final stage in my

transformation into a fan. One to two books a day for months and months on end, with

unceasing fervor and dedication. My great-grandmother must have smiled on me

benevolently from the Great Worldcon in the Sky where she went after giving up on the

mundane world at the age of 90. Grandmother did smile benevolently, even though

she apparently disbelieved the existence of so much SF in the world. Her disbelief was

abetted by the weird covers of my paperbacks; nothing that lurid could have been

serious, in her opinion. Mother did not smile benevolently; she was piqued. Only when

a flurry of small press publishers appeared here in the eighties and started flooding

the market with translated Angloamerican SF, did she forgive me for having the gall to

look where she could not.

I didn't care much about anyone's

opinion then. I read and read and read, trying to catch up on the thirty years of

American and British science fiction production that had passed me by. If I could, I

would have taken the books intravenously, or soaked them up through the skin; reading

was so damn slow. I'd have absorbed them whole, together with the bookworms.

In time, with enough bookworms ingested and accumulated, I'd have turned into a

bookworm myself, a giant obese Shai-Hulud of bookdom, burrowing deep down under the

library and bookstore basements, coming out in a geyser of bricks, parquet, and

hardcovers only to devour the latest skiffy releases. I didn't care much about anyone's

opinion then. I read and read and read, trying to catch up on the thirty years of

American and British science fiction production that had passed me by. If I could, I

would have taken the books intravenously, or soaked them up through the skin; reading

was so damn slow. I'd have absorbed them whole, together with the bookworms.

In time, with enough bookworms ingested and accumulated, I'd have turned into a

bookworm myself, a giant obese Shai-Hulud of bookdom, burrowing deep down under the

library and bookstore basements, coming out in a geyser of bricks, parquet, and

hardcovers only to devour the latest skiffy releases.

What saved me was supply-side economics.

It delivered a shock that brought me to my senses, kept me out of the claws of

depravity, and let me be just another ordinary fan. Namely, the book business went

soft in the early seventies and the foreign book bookstore a couple of blocks away

from my library decided to meet the challenge aggressively. They tried catering for a

wider clientele, especially in the paperback section of the store, and to that purpose

added several new genre lines to their usual choice of romances, gothics, and skiffy.

One of the new choices, to my amazement, was pornography. Overnight there was a whole

new section of shelving devoted to the Olympia Press "Traveller's Companion" line of

books, with color-coded covers. Green covers for "regular" sex, yellows for the gays,

pink for the kinks, etc. Some of the stuff was very good, too, exciting and

beautifully written. What saved me was supply-side economics.

It delivered a shock that brought me to my senses, kept me out of the claws of

depravity, and let me be just another ordinary fan. Namely, the book business went

soft in the early seventies and the foreign book bookstore a couple of blocks away

from my library decided to meet the challenge aggressively. They tried catering for a

wider clientele, especially in the paperback section of the store, and to that purpose

added several new genre lines to their usual choice of romances, gothics, and skiffy.

One of the new choices, to my amazement, was pornography. Overnight there was a whole

new section of shelving devoted to the Olympia Press "Traveller's Companion" line of

books, with color-coded covers. Green covers for "regular" sex, yellows for the gays,

pink for the kinks, etc. Some of the stuff was very good, too, exciting and

beautifully written.

Hm. I cannot say I turned from a SF fan

into a pornophile. No, I have always approved of explicit sex, in art and out of it,

and still do. And I never stopped reading science fiction. It is just that suddenly

there was a timely reminder of other things in life. Slowly I brought the reading pace

down to normal, the fever receded, and I stopped bearing Ghu's witness before the

world. Science fiction became Just A Goddam Hobby then, and has remained that ever

since. Hm. I cannot say I turned from a SF fan

into a pornophile. No, I have always approved of explicit sex, in art and out of it,

and still do. And I never stopped reading science fiction. It is just that suddenly

there was a timely reminder of other things in life. Slowly I brought the reading pace

down to normal, the fever receded, and I stopped bearing Ghu's witness before the

world. Science fiction became Just A Goddam Hobby then, and has remained that ever

since.

All illustrations by Teddy Harvia

|